CAIRO (Reuters) – Egypt is pushing to educate people in rural areas on birth control and family planning in a bid to slow a population growth rate that President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said poses a threat to national development.

The country is already the most populous in the Arab world with 93 million citizens and is set to grow to 128 million by 2030 if fertility rates of 4.0 births per thousand women continue, according to government figures.

In 2016, Egypt saw the birth of 2.6 million babies, the country’s statistics agency CAPMAS said last month.

“The two biggest dangers that Egypt faces throughout its history are terrorism and population growth and this challenge decreases Egypt’s chances of moving forward,” Sisi told a youth conference last month.

Egypt’s health minister last month started Operation Lifeline, a strategy to reduce the birth rate to 2.4 and save the government up to 200 billion Egyptian pounds ($11.3 billion) by 2030.

Its target is rural areas where many view large families as a source of economic strength and there is resistance to birth control because of a belief that it is unlawful under Islam to aim to conceive a specific number of children.

Egypt’s Al-Azhar University, a 1,000-year-old seat of Islamic learning, endorsed the ministry’s plan and said family planning is not forbidden.

Ousted President Hosni Mubarak and his wife Suzanne set up a population control program decades ago but this is the first time the government says it is motivated by concern that rapid expansion saps the economy.

FREE CHECK-UPS

The health ministry said it would deploy 12,000 family planning advocates to 18 rural provinces but gave no details of how it would attract more women to the program.

The ministry runs nearly 6,000 family planning clinics where women receive free check-ups and can buy heavily subsidized contraceptives ranging from condoms at 0.10 Egyptian pounds to copper Intrauterine Devices at 2 Egyptian pounds.

“Given how expensive the cost of living has become and the increase in prices, people have started becoming more aware. They know they can afford to have one or two children, but no more,” Ahlam Saad, a nurse at a government-run family planning clinic on the outskirts of Cairo, told Reuters.

Inflation has surged in Egypt to record highs over the past year after the country floated its currency in November, a move which drove down the value of the pound.

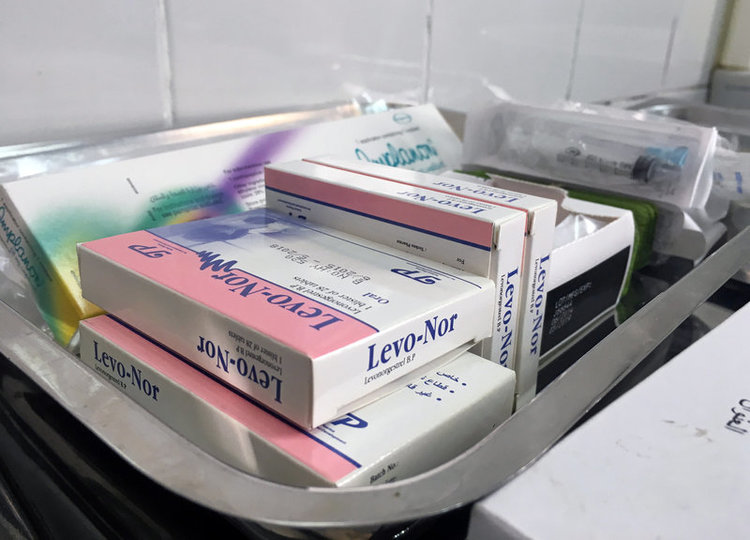

That drop created a shortage of medicines in pharmacies across Egypt, as scores of products including contraceptives became unprofitable to produce or import.

“My fiance and I decided that we want to delay having a baby, I want to continue my studies and we’re just not ready,” said 30-year-old Sherin who sat in the waiting room with a score of others.

In line with government plans to reduce reliance on imports, the ministry contracted Acdima International, a subsidiary of the privately owned Arab Company for Drug Industries and Medical Appliances, to source locally produced hormonal contraceptives.

The deal saves the government millions of dollars and covers 65 percent of local demand, Managing Director Tarek Abulela said, adding that the rest is exported throughout the region.

($1 = 17.7100 Egyptian pounds)